Natura ed Arte era una rivista culturale italiana pubblicata con cadenza quindicinale verso la fine del XIX secolo, che trattava di tematiche relative all'arte, alla moda e al buon vivere.

Siamo nella fine dell'800, dunque il periodo di massima diffusione di assenzio, e sul numero pubblicato 15 settembre 1894 c'è un articolo di R. Raqueni dal titolo "Vita parigina", nel quale viene raccontata la vita a Parigi, e in generale nella Francia di quel periodo. L'articolo si apre con questi due argomenti dal titolo L'ora dell'assenzio e L'absintheur (ovvero L'assenziofilo)

Di seguito riportiamo l'immagine della rivista originale, la sua trascrizione, ed anche una nostra traduzione in inglese.

![]()

Vita parigina

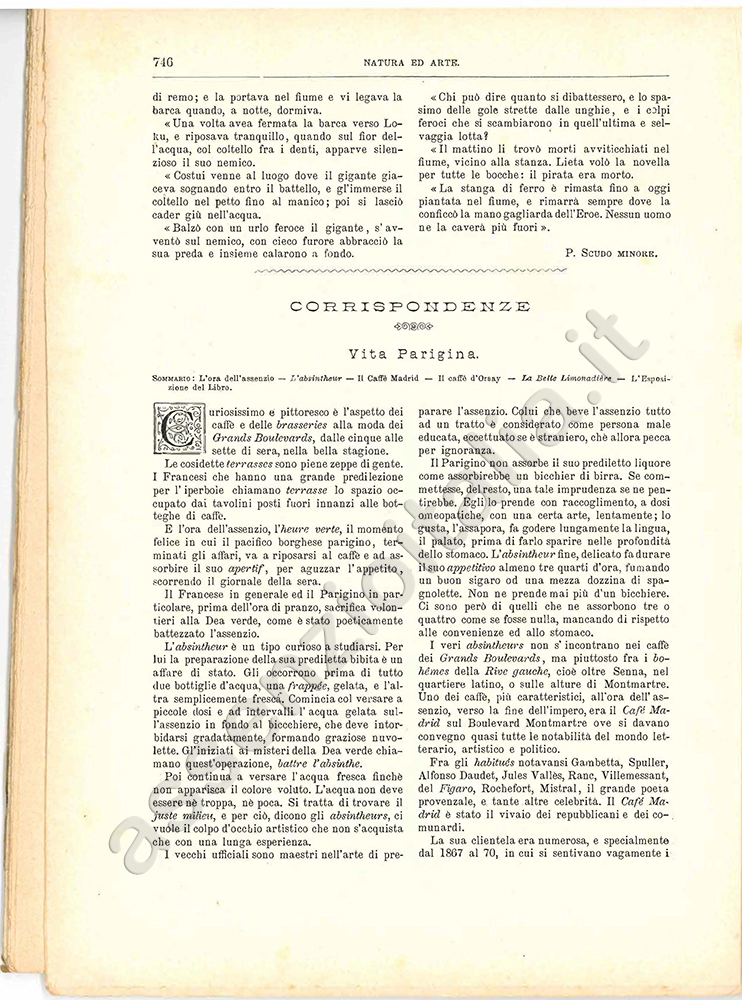

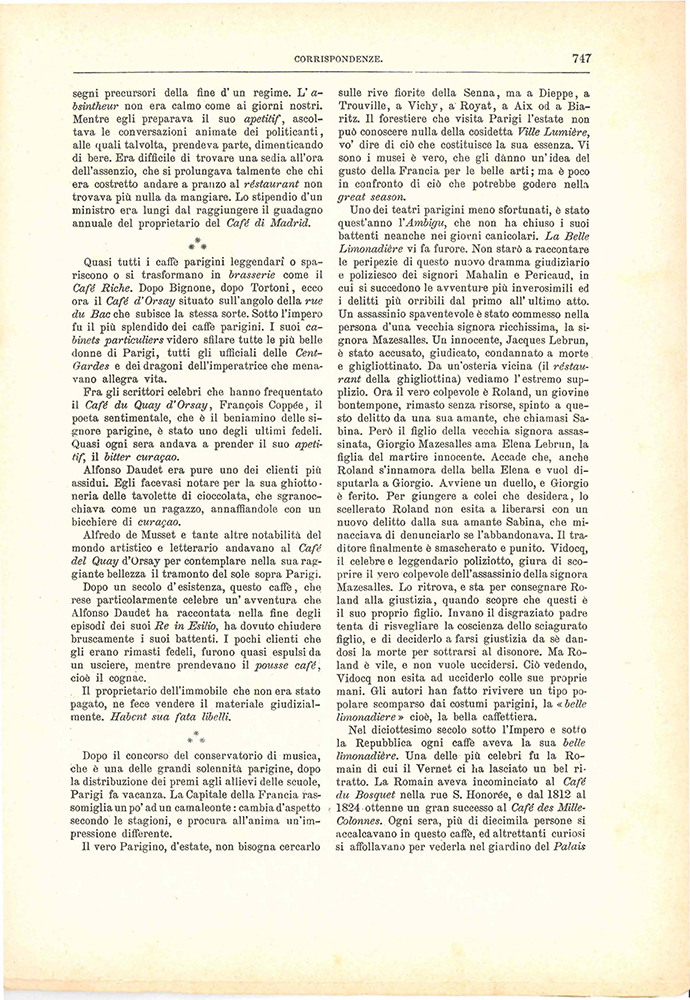

Sommario: L’ora dell’assenzio – L’absintheur – Il Caffè Madrid – Il caffè d’Orsay – La Belle Limonadièere – L’esposizione del Libro

Curiosissimo e pittoresco è l’aspetto dei caffè e delle brasseries alla moda Grand Boulevards, dalle cinque alle sette di sera, nella bella stagione. Le cosiddette terrasses sono piene zeppe di gente.

I Francesi che hanno una grande predilezione per l’iperbole chiamano terrasse lo spazio occupato dai tavolini posti fuori innanzi alle botteghe di caffè.

E l’ora dell’assenzio, l’heure verte, il momento felice in cui il pacifico borghese parigino, terminati gli affari, va a riposarsi al caffè e ad assorbire il suo aperitif, per aguzzar l’appetito, scorrendo il giornale della sera.

Il Francese in generale ed il Parigino in particolare, prima dell’ora di pranzo, sacrifica volontieri alla Dea verde, come è stato poeticamente battezzato l’assenzio.

L’absintheur è un tipo curioso a studiarsi. Per lui la preparazione della sua prediletta bibita è un affare di stato. Gli occorrono prima di tutto due bottiglie d’acqua, una frappée, gelata, e l’altra semplicemente fresca. Comincia col versare a piccole dosi e ad intervalli l’acqua gelata sull’assenzio in fondo al bicchiere, che deve intorbidarsi gradatamente, formando graziose nuvolette. Gl’iniziati ai misteri della Dea verde chiamano quest’operazione, battre l’absinthe.

Poi continua a versare acqua fresca finché non apparisca il colore voluto. L’acqua non deve essere né troppa, né poca. Si tratta di trovare il juste milieu, e per ciò, dicono gli absintheurs, ci vuole il colpo d’occhio artistico che non s’acquista che con una lunga esperienza.

I vecchi ufficiali sono maestri nell’arte di preparare l’assenzio. Colui che beve l’assenzio tutto ad un tratto è considerato come una persona male educata, eccettuato se è straniero, ché allora pecca per ignoranza.

Il Parigino non assorbe il suo prediletto liquore come assorbirebbe un bicchier di birra. Se commettesse, del resto, una tale imprudenza se ne pentirebbe. Egli lo prende con raccoglimento, a dosi omeopatiche, con una certa arte, lentamente; lo gusta, l’assapora, fa godere lungamente la lingua, il palato, prima di farlo sparire nelle profondità dello stomaco. L’absintheur fine, delicato fa durare il suo appetitivo almeno tre quarti d’ora, fumando un buon sigaro od una mezza dozzina di spagnolette. Non ne prende mai più d’un bicchiere. Ci sono però di quelli che ne assorbono tre o quattro come se fosse nulla, mancando di rispetto alle convenienze ed allo stomaco.

I veri absintheurs non s’incontrano nei caffè dei Grands Boulevards, ma piuttosto fra i bohèmes della Rive gauche, cioè oltre Senna, nel quartiere latino, o sulle alture di Montmartre. Uno dei caffè, più caratteristici, all’ora dell’assenzio, verso la fine dell’impero, era il Café Madrid sul Boulevard Montmartre ove si davano convegno quasi tutte le notabilità del mondo letterario, artistico e politico.

Fra gli habitués notavansi Gambetta, Spuller, Alfonso Daudet, Jules Vallès, Ranc, Villemessant, del Figaro, Rochefert, Mistral, il grande poeta provenzale, e tante altre celebrità. Il café Madrid è stato il vivaio, dei repubblicani e dei comunardi.

La sua clientela era numerosa e specialmente dal 1867 al 70, in cui si sentivano vagamente i segni precursori della fine d’un regime. L’absintheur non era calmo come ai giorni nostri.

Mentre egli preparava il suo aperitif, ascoltava le conversazioni animate dei politicanti, alle quali talvolta, prendeva parte, dimenticando di bere. Era difficile trovare una sedia all’ora dell’assenzio, che si prolungava talmente che chi era costretto andare a pranzo al réstaurant non trovava più nulla da mangiare. Lo stipendio d’un ministro era lungi dal raggiungere il guadagno annuale del proprietario del Café di Madrid.

"Natura ed Arte" - anno III 1894 - n.20 Settembre 15

Casa Editrice Dott. Francesco Vallardi. Roma - Milano

![]()

Parisian Life

Summary: Absinthe Hour - L'absintheur - Madrid Café - Orsay Café - La Belle Limonadièere - The Book Exhibition

The look of cafés and brasseries is very curious and pittoresque, in the Grand Boulevards style, from five to seven in the evening, during the warm season. The so-called terrasses are packed with people. Those French who have a great predilection for hyperboles call terrasse the space taken by the tables placed outside in front of the coffee shops.

It’s the absinthe hour, the heure verte, the happy moment when the peaceful parisian bourgeois, after finishing his business, goes to rest at the café and have his aperitif to whet his appetite, scrolling through the newspaper of the evening.

The French in general and the Parisian in particular, before lunchtime, willingly sacrifice to the Green Goddess,

the way absinthe has been poetically baptized.

The absintheur is himself a curious type to study. For him, the preparation of his favorite drink is a state affair. He first needs two bottles of water, a frappée, a frozen one and another simply fresh one. It begins by pouring ice-cold water in small doses and at intervals over the absinthe resting at the bottom of the glass, to roil it gradually, by forming cute little clouds. The initiates into the mysteries of the Green Goddess call this operation beating the absinthe..

He then continues to pour fresh water in until the desired color appears. There has to be neither too much nor too little water. It’s a matter of finding the juste milieu, and to get to that, the absintheurs says, it takes an artistic glance that can only be acquired through a long expertise. Old officers master the art of preparing absinthe. The one who drinks absinthe in one sip is considered as an ill-mannered person, except if he’s a foreigner, who then sins out of ignorance. The Parisian does not consume his favorite liqueur as he would drink a glass of beer. Moreover, if he committed such imprudence, he would definitely regret it. He sips it with mindfulness, in homeopathic doses, with a certain art, slowly; he tastes it, savors it, makes the tongue and the palate enjoy it for a long time, before making it disappear deep in the stomach. The refined and dainty absintheur makes his appetite last at least three quarters of an hour, smoking a good cigar or half a dozen espagnolettes. He never drinks more than a glass. There are, however, the ones who take three or four of them as if they were nothing, disrespecting the customs and their stomach.

The real absintheurs don’t meet in the cafes along the Grands Boulevards, but rather among the bohèmes of the Rive gauche, which are, beyond the Seine, in the Latin Quarter, or on the heights of the Montmartre. One of the most characteristic cafes, for the absinthe hour, towards the end of the empire, was the Café Madrid on Boulevard Montmartre, where almost all the notables of the literary, artistic and political world, used to meet. Among the habitués you would spot Gambetta, Spuller, Alfonso Daudet, Jules Vallès, Ranc, Villemessant, of the Figaro, Rochefert, Mistral, the great provencal poet, and many other celebrities. Madrid Café was the hatchery for the Republicans and the Communards. Its clientage was numerous, especially from 1867 to 70, when premonitory signs of the regime's end were vaguely felt.

The absintheur was not as calm as he is today. While preparing his aperitif, he listened to the heated conversations of the politicians, in which he sometimes took part, forgetting to drink. It was difficult to find a chair during the absinthe hour, which would take so long that those who had to go to have lunch at the restaurant couldn't find anything to eat. A minister’s salary was no way close to the annual profit of the Madrid Café’s owner.

![]()

"Natura ed Arte" (Nature and Art) - year III 1894 - n.20 September 15

Publishing house Dott. Francesco Vallardi. Roma - Milano